How are US Attitudes toward US Military Policy Changing?

Political Differences and an "Age of Trump" Effect?

I am beginning a project where I investigate differences in attitudes toward war and the military in the United States. This may evolve into something academic, but I am more interested in popular-level discourse on this topic. I am interested in debates on militarism supposedly fracturing the Democratic Party and claims of renewed anti-war sentiment in the GOP. Finally, whether or not there is a surge in military skepticism in the GOP, I want to know who the anti-war Republicans and conservatives are. I intend to publish a series of short articles where I walk through my steps in data analysis. I will begin with some standard findings and close on more interesting content.

The first thing I did was investigate whether or not there have been meaningful changes in attitudes toward the military in recent years. I utilized data from the Voter Study Group and the General Social Survey, the latter being considered the “gold standard” (alongside the US Census) in US sociology. While no dataset comprehensively covers all of the important attitudes people have toward war and conflict, I believe this is a good place to stop.

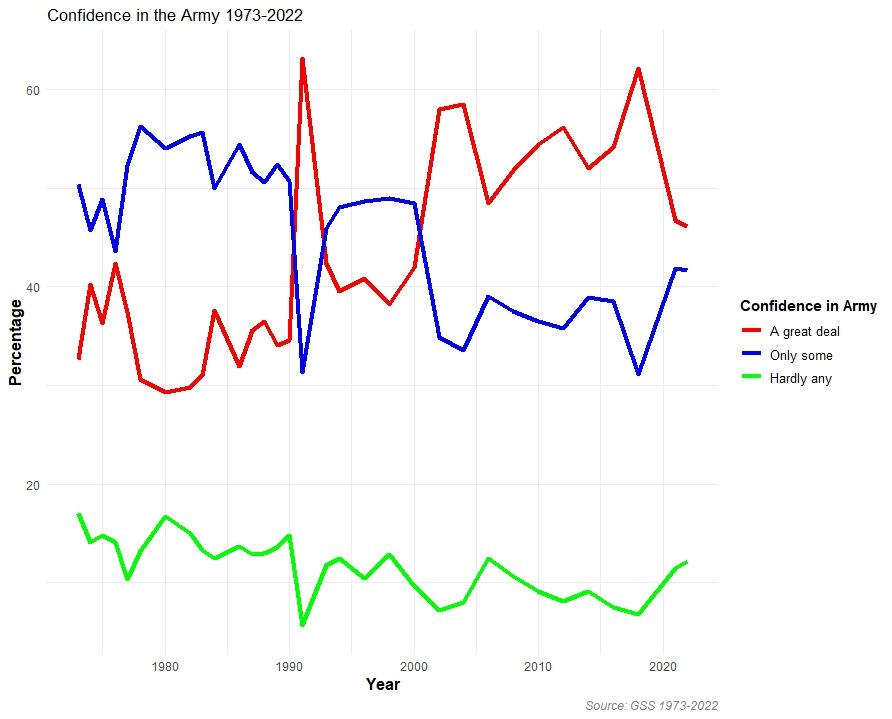

Looking at changes in confidence in the army since 1973, it is difficult to claim that there is any “age of Trump” effect going on. The lowest levels of military support are found throughout the 1980s. The military’s reputation reached a peak high in 1991 (60.7% reporting a great deal of confidence). Support has waxed and waned since, but it has never returned to the low 30s as seen in the 1980s. The variance since 2016, or “the age of Trump,” has been wide. Support for the military increased in 2016 and reached a near peak high in 2018 (60.63% reported a great deal of support). Confidence in the military has decreased since then, but not to anything close to record lows.

Examining preferences for military spending policies yields some differences, which we’ll need to address momentarily, but it also fails to support an “age of Trump” effect. Between 2014-2016, which mostly covers an election season, the percentage of people in the US who believed the government was spending too much on the military decreased by about four percentage points. Following the 2016 election, there is not even a 1% change here. In that two-year stretch, US satisfaction with military spending, indicated by those reporting that our spending was “about right” increased by about 5-6%.

There is some change in the early 2020s. While those who report that military spending is “about right” remains steady, probably caused by attrition from the “too little” camp, believe that we are spending too much does increase by about 6-7%.

In the next series of posts, I will share my investigations into how these changes occur among party lines. Even if national averages do not tell us an “age of Trump” story, it is possible that the Trump years are associated with significant changes among electorally significant subgroups. Traditionally, progressive sentiment is associated with military skepticism and anti-war preferences in the United States. Still, the US right wing has always had non-interventionist, isolationist, or “America first” contingents who prefer the US not engage in foreign military conflicts, and some conventional peace activists are attracted to mainstream conservatism and libertarian politics as well. In recent years, national conservatives rallying around figures like Tucker Carlson and new “Buchananites” have claimed to have taken the mantle of peace activism from the left and found themselves in (supposedly) strange alliances with progressive and leftist activists (these labels are often reasonably disputed) such as Glenn Greenwald, Aaron Mate, Ben Norton, and Tulsi Gabbard. Progressive and leftist dissent often claims that in response to Trump’s supposed non-interventionist preferences (I dispute that he has such preferences) the Democratic Party and conventional US liberals have increased their commitments to militarism. Breaking down attitudes toward the military by party affiliation and ideological preferences can help adjudicate these claims.

It is important to note that we are not working with direct proxies of preferences for war or satisfaction with US military endeavors. This is made clear when comparing our two measures, where sometimes dissatisfaction with the military increases alongside preferences for greater funding. Nonetheless, this is a good place to begin exploring changes in attitudes toward US military policy over time.